(Re)discovering Roman tureen vase-urns in calcite alabaster

…and the importance of technology

by Simona Perna

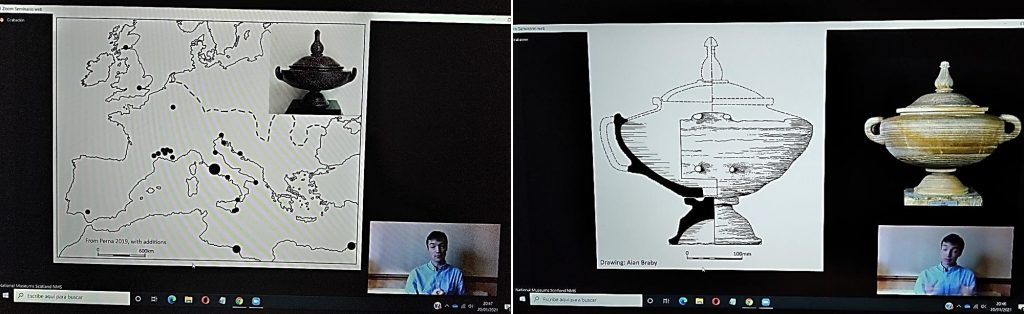

On 20/01/21 the National Museum of Scotland aired a special online event organised by two of its curators, Dr Fraser Hunter, Principal Curator of Iron Age and Roman collections, and Dr Dan Potter, Assistant Curator of Ancient Mediterranean collections, who talked about a large fragment of a Roman alabaster funerary urn – of the type I have labelled ‘tureen’ for the formal similarity to a modern soup bowl – found near the Roman fort of Camelon along the Antonine Wall (Scotland) in 1849 and recently rediscovered by Dr Hunter among the ‘forgotten’ pieces of the museum’s collection.1 The urn is on display for a temporary exhibition at the museum. The presentation, followed by a panel discussion and Q&A live session, was chaired by award-winning historian, author and broadcaster Professor Bettany Hughes. The lecture was great! The fact that it was a free online event and people from all over the world could take part showed how, in times like these, technology can cut distances and allow us back into a museum, albeit virtually!

The Scottish ‘tureen’ urn is truly remarkable

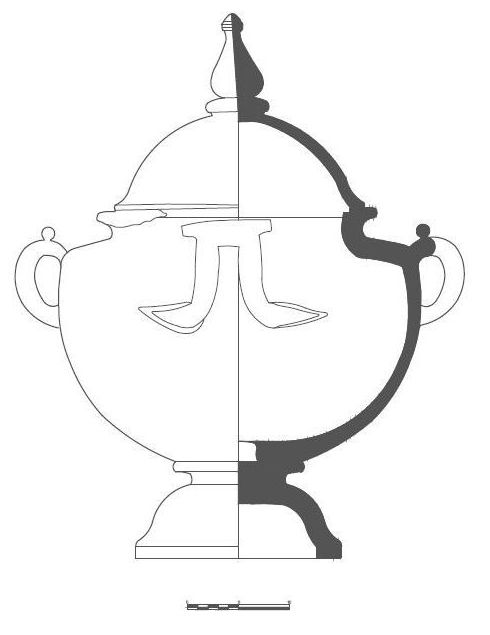

The Scottish ‘tureen’ urn is truly remarkable. Unfortunately, all is left of it is a large portion of its body and ‘bell’ foot on which it rests, but this is enough to establish that is another, astonishing example to add to the list of a small group of funerary urns or tureens. These rarer ash containers carved from exotic Egyptian stone – calcite alabaster, porphyry, granite and basalt – were produced and used in the Julio-Claudian period by the richest and some of the most important people of the empire. Unfortunately, nothing is known of the actual archaeological context of the Scottish urn, but given its discovery near a Roman military fort it is quite likely that it had housed the remains of someone quite high-up in the local military hierarchy, an important commander or someone related to them!

These urns were the focus of my doctoral research, which expanded a preliminary catalogue I compiled of them for my BA/MA dissertation. The impact that past illegal excavations, private collecting, antiquities black market and the lack of an analytical framework had on the history of these urns in modern times meant that the few known examples had been studied from an often exclusive, taxonomical perspective. Starting from some 30 urns or so – I managed to gather and catalogue more than 70! More importantly, their re(discoveries) continue, as in the case of the Scottish urn, and every time a new one ‘pops up’ I get very excited and I immediately add it to my catalogue (which is probably the reason why it is taking me so long to publish it!).

The lecture was great!The fact that it was a free online event and people from all over the world could take part showed how, in times like these, technology can cut distances and allow us back into a museum, albeit virtually!

When Dr Hunter contacted me in 2019 about his exciting (re)discovery I was thrilled: one because there was only anther one of such ‘special’ urns discovered in Britain2; two because Scotland was the northernmost find-spot – the geographic distribution of tureens seems to have been limited to the South-Western provinces of the Roman empire3 – and three because the surviving foot confirmed what I had hypothesised regarding the carving techniques – elements worked separately and then added to the rest of the urn!4This latter detail was particularly important seeing as most of the examples I catalogued had been restored in the past, meaning that the foot had been permanently ‘glued’ to the body, thus hindering a detailed investigation of the carving techniques. Dr Hunter, who was writing the entry for the urn for an upcoming publication at the time – found out about my work. He was very kind to share the news with me and to ask my opinion regarding the urn!

These rarer ash containers carved from exotic Egyptian stone – calcite alabaster, porphyry, granite and basalt – were produced and used in the Julio-Claudian period by the richest people of the empire

Starting from some 30 examples or so – I managed to gather and catalogue more than 70!

How excited – and proud if I may – I felt as my work was being cited by Dr Fraser during his public lecture! I felt like my work and passion for these objects were being recognised – but this should not have surprised me! Is it not what research is really about, to generate knowledge that can – and must – be shared and accessed by everyone?!

Is it not what research is really about, to generate knowledge that can – and must – be shared and accessed by everyone?!

TECHNET, my current MSCA funded project, as its manifesto states, is about understanding and assessing the level of technological innovation and artisan interaction in the production of stone vases in the Greco-Roman period. However, what underlies its hypotheses is my previous study of these vase urns, whose production shows a remarkable technological input, something different from contemporary Roman sculpture. These vase-urns resulted from cross-craft interaction and the application of sophisticated technologies, such as the lapidary lathe. Interestingly, the level of innovation their manufacture involved – for the early Imperial period – appears to have been going hand in hand with traditional techniques, the ancestral heritage of stone artisans trained and formed within diverse carving traditions that converged into one.

These vase-urns resulted from cross-craft interaction and the application of sophisticated technologies, such as the lapidary lathe

My point was: which carving traditions? Calcite alabaster is the preferred stone type for these urns, something which clearly hinted at an Egyptian ethnic origin of the artisans, but the shape is a Classical one, plus certain carving techniques are not exclusive to Egypt and find parallels in Greek stone vases, like the beautiful white marble pyxides, from the 5th-4th c. BC, thus the artisans making the tureens must have been familiar with all of these techniques.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/255613

Moreover, not just the tureens, but a whole series of contemporary vases in imported decorative stone suddenly appear in the early Imperial period. Indeed, stone vase making does not strike us as a typically Roman craft and therefore, at first, it must have required a new technological input possibly from foreign artisans and transfer of know-how to local ones. So, questions began to arise: who were these objects made by? How and when was technology transferred between artisans? To what extent was Roman technology affected by foreign technology, and above all, where did the technology and know-how originate? These were some of the questions that led me to expand the field of enquiry to the Greek and Hellenistic periods and inspired my current project, whose aim is to see how far we can take the evidence on these three stone vase ‘traditions’ and what we can infer from them about technological innovation and knowledge transfer in the past. But this is something I will discuss in my future blogs as my research moves forward!

So, for more news on my project and Greco-Roman stone vases stay tuned or follow us on Twitter TECHNET PROJECT (MSCA-2019-895286) News and Feeds

For more bibliography on the tureen vase-urns check https://icac.academia.edu/SimonaPerna

or see my profile on the ‘Research team’ page.

Footnotes

- Hunter, f. (2020) ‘‘… one of the most remarkable traces of Roman art … in the vicinity of the Antonine Wall.’ A forgotten funerary urn of Egyptian travertine from Camelon, and related stone vessels from Castlecary’, in D. J Breeze and W. S. Hanson (eds) The Antonine Wall: Papers in Honour of Professor Lawrence Keppie. Oxford: Archaeopress, 233-253.

- Perna, S. (2015) ‘Cinerary urns in coloured Egyptian stone’, in P. Coombe, M. Henig, F. Grew and K. Hayward (eds.), Roman Sculpture from London and the South-East. Corpus Signorum Imperii Romani, Great Britain, Vol.1: Fascicule 10, OUP/British Academy: 126-131.

- Perna, S. (2019) The social value of funerary art. Burial practices and tomb owners in the provinces of the Roman empire, in Porod, B – Scherrer, P (eds) Akten des 15. Internationalen Kolloquiums zum Provinzialrömischen Kunstschaffen.Der Stifter und sein Monument Gesellschaft – Ikonographie – Chronologie.14. bis 20. Juni 2017 Graz / Austria.

- Perna,S., «A Case of Serial Production? Julio-Claudian “tureen” funerary urns in calcitic alabaster and other coloured stone» a Reinhardt, A. B. (ed.), Strictly economic? Ancient Serial Production and its Premises. Proceedings of Panel 3.18, 19th International Congress of Classical Archaeology (Cologne/Bonn (Alemanya), del 22 el 26 May 2018), Archaeology and Economy in the Ancient World 20, Propylaeum, Heidelberg, p. 5-17.